California Association of Criminalists

Since 1954

WHAT IS A CRIMINALIST?

A criminalist has a background in science, typically having at least a baccalaureate degree in an area such as chemistry, biology, forensic science, or criminalistics. Some criminalists have degrees in other, similarly related areas. Many criminalists have advanced degrees.

With the above scientific background and additional training given by his/her employer (either a government or private laboratory) a criminalist applies scientific methods and techniques to examine and analyze evidentiary items and testifies in court as to his or her findings. Please read below, under criminalistics, for a more detailed description of what different types of criminalists do in the laboratory.

WHAT IS THE CAC?

The California Association of Criminalists (CAC) is a professional membership organization of forensic scientists. It was founded in 1954 by sixteen members from various agencies throughout California. They met to exchange ideas, new testing methodologies, and to share case histories. Since its inception, the CAC has expanded its membership throughout the United States and Europe. The CAC is the oldest established regional forensic science organization in America. CAC Members are employed in local, state, and federal governmental agencies, as well as private companies and teaching institutions.

Today, there are many members representing an array of forensic science specialties. They include criminalists, document examiners, serologists, toxicologists, chemists, molecular biologists, firearm and toolmark examiners, and educators. CAC members are involved in national and international forensic science organizations such as AAFS, AFTE, ANAB, and IAI. CAC membership provides an opportunity to be involved in the professional activities that develop and contribute to one's career, the profession of criminalistics, and the criminal justice system.WHAT ARE SOME TYPES OF CRIMINALISTICS?

Firearms and Toolmarks

Firearm and toolmark examiners provide information to investigators about the caliber and type of firearm used in a crime. Individual marks, or striations, are left on bullets by the barrel of a firearm. Once a firearm is recovered, the individual marks on the test-fires are compared to the individual marks on the evidence. This comparison can identify a bullet or cartridge case as being fired by a particular firearm. Similarly, tools used in crimes can leave striations and other marks on surfaces. These marks can be compared to the tool believed to have made them. If the comparison is a positive match, a tool may be identified as having made the mark. A national computer database (NIBIN) of marks on cartridge cases and bullets has been developed to link a particular firearm to previously unrelated crimes.

Trace Evidence

Trace evidence, frequently overlooked because of its microscopic size, applies microanalysis to fibers, hair, soil, paint, glass, pollen, explosives, gunshot residue, food, plastic bags, and virtually anything involved in a crime. No training exists that will prepare the trace evidence analyst for every kind of case that will cross their workbench, as each case is fascinatingly unique. By having a thorough knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of microscopic, spectroscopic, and chromatographic methods, the trace evidence examiner can meet the analytical challenge of each case.

DNA and Serology

In the mid 1980s, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis techniques began to be applied to forensic cases. Tissue and fluids from the body carrying the genetic code of DNA may be used to compare to a known standard. This can possibly allow blood and other biological material to be associated with an individual. Databases of DNA profiles (CODIS) have been compiled to aid in identifying criminals and have been used to solve cases many years old, where samples were properly preserved and re-analyzed. In some cases, innocent persons have even been released from prison based on the re-analysis of DNA evidence.

Drugs, Alcohol and Toxicology

The criminalist uses a battery of analytical tools and their knowledge of chemistry to identify controlled substances in powders, pills, liquids, and body fluids. A criminalist may be called to a clandestine laboratory by investigators, where illegal drugs are produced. Criminalists are frequently responsible for maintaining breath alcohol analysis instruments and training laboratory technicians and police officers who run the tests on drivers suspected of DUI. Sometimes, no controlled substance is present and sometimes more than one kind of drug can be detected in a sample.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A CRIMINALIST AND A CRIMINOLOGIST?

Criminalistics is one of many divisions in the field of forensic science. Forensic science includes forensic pathology, odontology, entomology, accounting, engineering, criminology, and other disciplines. All of these are specialized sections in forensic science. Specifically, criminalists use techniques learned in chemistry, physics, material sciences, molecular biology, geology, and other physical scientific disciplines to assist in the investigation of crimes. After completing the laboratory work and writing up a report summarizing their findings, the criminalist may testify in a court of law. They must be able to communicate their conclusions in a way that the judge, attorneys, and jury can plainly understand.

Criminalistics should not be confused with the field of criminology. Criminologists are sociologists, psychologists, and others who study the causes and effects of crime on society.

WHAT ABOUT CSI? HOW REAL IS IT?

Crime scene investigation is not as glamorous, fast, or easy as it is depicted on television! It is, however, fulfilling and rewarding work.

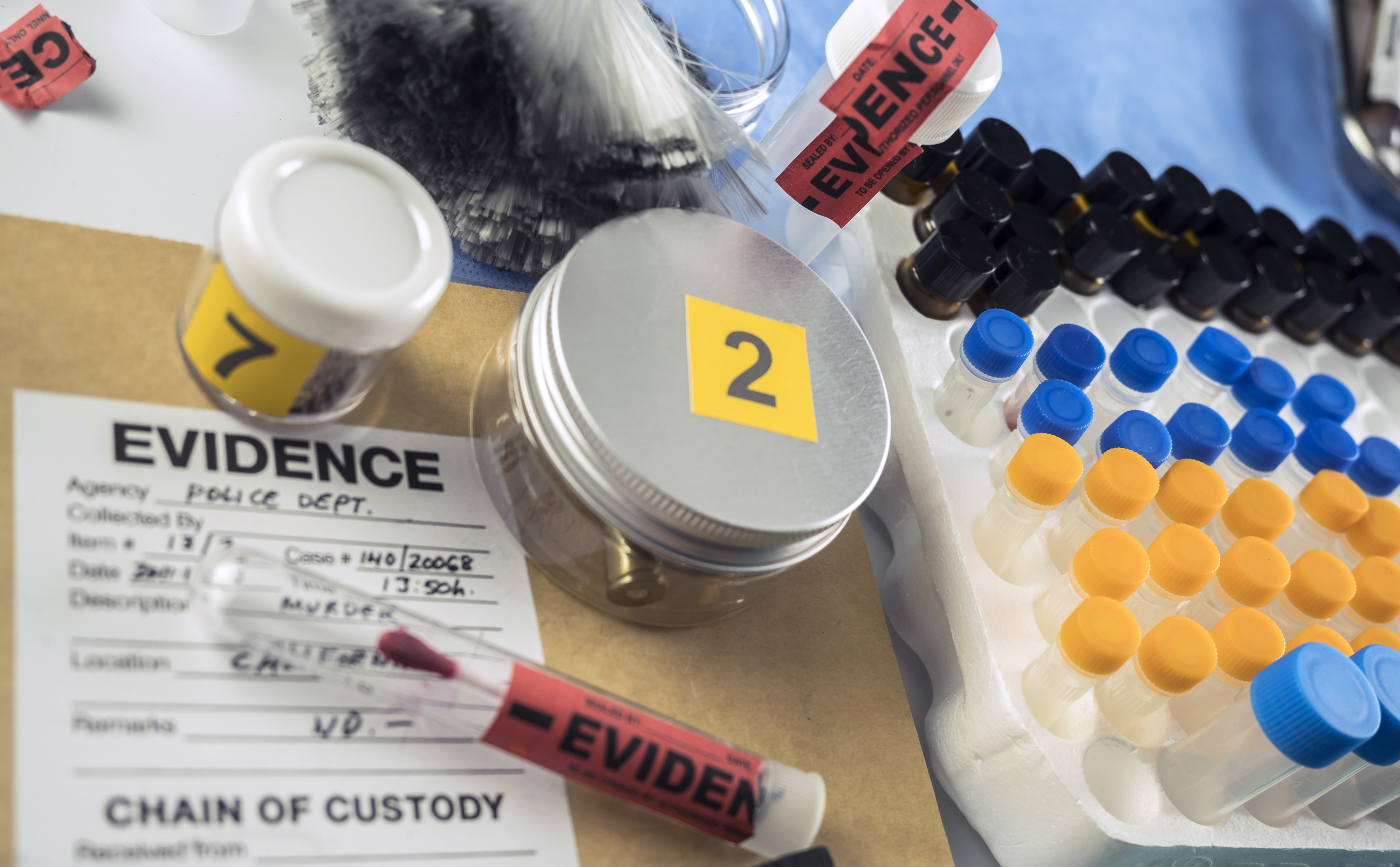

For the crime scene investigator, examination involves the recognition, documentation, collection, preservation, and interpretation of physical evidence which may be as big as a truck or as small as a diatom or pollen grain. Understanding the physical relationship between evidence at the scene or recovered at a search warrant, keen observation of items out of place, the altered condition of items, or items possibly added to the crime scene are important skills of crime scene investigation. The investigator collects, documents, preserves, and makes interpretations about the evidence and their relationship to the series of events that occurred during the crime.

The crime scene investigator or forensic evidence technician brings evidence back to the laboratory where additional examinations will be conducted by the relevant sections of the laboratory. Conclusions are made about the incident by associating particular items of evidence to specific sources and reconstructing the crime scene. This means not only associating a suspect with a scene but also the telling of a story about what transpired before, during, and after the crime. The investigator must work cooperatively with various sections of the laboratory in order to compile and organize the results, reconstruct the scene, and draw conclusions relating to the events of the crime. By collecting and applying a broad spectrum of knowledge and techniques, the crime scene investigator will associate and identify relevant evidence, interpret the results, reconstruct the crime scene, write a report summarizing the findings, and testify in court.